Vietnam Protest Movement: A Defining Moment in Australia’s History

As the Vietnam War dragged on, Australians began to question the initial justifications for their country’s involvement. The fear that communism, particularly from China, posed a direct threat to Australia had been a strong motivator early in the conflict. However, as the war progressed and national servicemen began to suffer casualties, public support started to wane.

In 1966, Prime Minister Harold Holt visited Washington and assured President Lyndon B. Johnson that Australia was “all the way with LBJ.” This declaration reflected the strong public backing of the war at that time. When President Johnson visited Australia later that year, he was greeted by large, enthusiastic crowds. Yet, even then, there were signs of dissent, with militants throwing paint and rotten eggs at the President’s limousine and making death threats, though these incidents were isolated.

Despite growing unease, Vietnam and conscription did not prevent Holt’s Liberal-Country Party coalition from winning a landslide victory in the October 1966 election. However, beneath the surface, a significant anti-war movement was beginning to take shape, driven primarily by the younger generation. Baby boomers, particularly university students, became the backbone of this opposition, viewing Vietnam as a disastrous policy pursued by an arrogant, conservative government. As the war dragged on with no clear end in sight, a broader spectrum of Australians began to oppose the war on moral grounds.

The Impact of Television on Public Perception

The Vietnam War became known as the “television war” due to the extensive coverage it received on television. Australians and Americans alike were regularly exposed to graphic images of the conflict, which starkly highlighted the suffering endured by those in Vietnam. The My Lai massacre in March 1968, where a company of U.S. troops murdered 347 civilians in the South Vietnamese hamlet of My Lai, further eroded public support for the war. The atrocity cast doubt on the war’s stated goals of protecting South Vietnam and halting the spread of communism. It also led Australians to question whether their soldiers might be committing similar acts.

By January 1970, the U.S. and Australia were both showing signs of withdrawing from Vietnam, though no specific exit dates had been set. Australia’s position was clearly tied to U.S. actions, leaving many Australians anxious about the future.

The Moratorium Movement

In early 1970, anti-war groups from across Australia convened in Melbourne and agreed to hold a “moratorium,” a term signifying a halt to business as usual. This movement was inspired by a similar U.S. moratorium in October 1969, where over 500,000 Americans protested in 1,200 cities and towns. The Australian moratorium became the largest and most sustained protest movement in the country’s history, with two primary objectives: the withdrawal of Australian troops from Vietnam and an end to conscription.

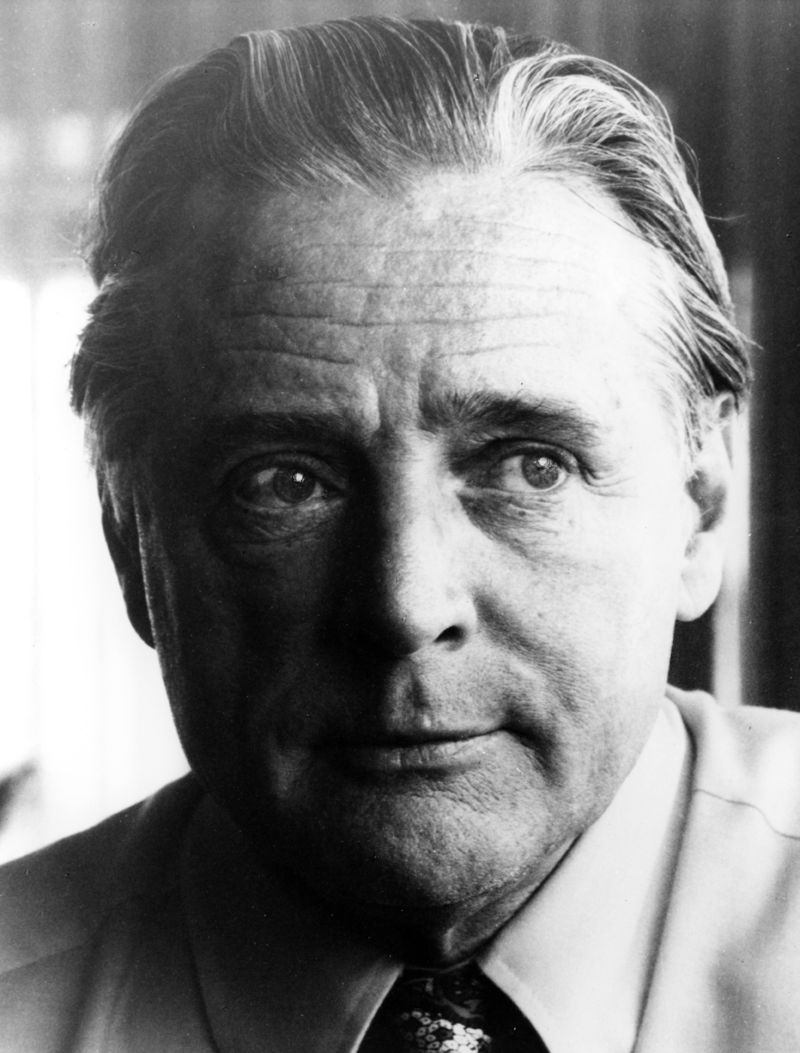

The movement gained momentum after the Coalition’s victory in the 1969 election, which signalled to many that government policy on Vietnam was unlikely to change for at least three more years. Dr. Jim Cairns, the Shadow Minister for Trade and Industry, emerged as the most visible leader of the moratorium movement. His charisma and intellect galvanized thousands of activists, and he emphasized the importance of maintaining non-violence during the protests.

The moratorium brought together a diverse coalition of groups opposed to the war, including clergy, teachers, academics, unions, politicians, and students. Donations poured in, and while university students had been at the forefront of the anti-war movement, the moratorium attracted thousands of everyday, middle-class Australians. Not everyone supported the movement; its size and intensity were unsettling to many, particularly conservatives like Billy Snedden, the Minister for Labour and National Service, who derided the protesters as “political bikies who pack-rape democracy.”

Despite this opposition, the first moratorium, held in May 1970, was a resounding success. Around 200,000 people participated, with the largest demonstration in Melbourne, where 70,000 people marched peacefully down Bourke Street, led by Cairns. The police remained restrained, and the crowds cheered the demonstrators on. Similar events took place across the country, in cities and rural towns alike.

The second and third moratoriums, held on 18 September 1970 and 30 June 1971, respectively, saw a shift in tone. Left-wing extremists dominated these later protests, leading to smaller turnouts and, in the case of the second moratorium, violence. In Melbourne, police baton-charged protesters, and in Sydney, 173 people were arrested.

The Fallout for Returning Soldiers

The My Lai massacre and the growing anti-war sentiment shifted the focus of many protesters away from the government and onto the soldiers themselves. Unlike the veterans of World War I and II, who were welcomed home as heroes, Vietnam veterans were often met with hostility. Some were spat on, insulted, and even rejected by branches of the Returned Servicemen’s League. This treatment had a severe psychological impact on many veterans, compounding the trauma they had already experienced in Vietnam.

A Defining Moment for Australia

While the moratoriums may not have directly influenced the government’s decision to withdraw troops—Prime Minister John Gorton had already begun the process before the protests—the movement undoubtedly reflected and reinforced a broad collapse in public support for the war. The moratoriums also influenced government policy on conscription, with Cabinet taking steps to reduce the number of draft resisters sent to jail following the first moratorium.

The moratoriums were a defining moment in Australia’s history, marking a significant shift in public attitudes toward authority and war.