Vietnam War’s Inaugural Medal of Honor Awardee, Roger H.C. Donlon, Passes Away.

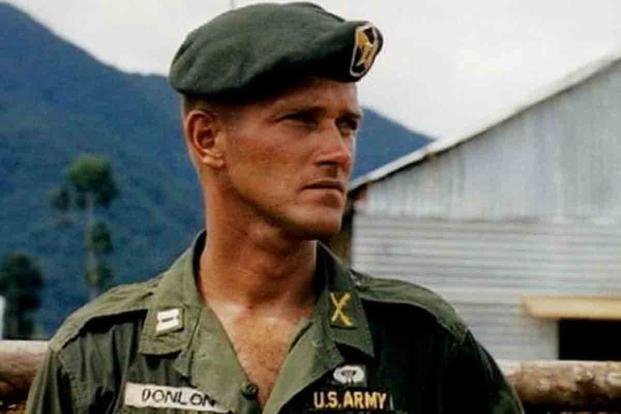

Photo: Then-Capt. Roger H.C. Donlon in Vietnam. (U.S. Army)

Upon enlisting in the Army in 1958, Roger H.C. Donlon, already acquainted with military life from a stint in the Air Force in 1953, embarked on a journey that would lead him to become the first Medal of Honor recipient of the Vietnam War. Leaving the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1957 after initially enrolling, Donlon chose to pursue his destiny in the Army. Following Officer Candidate School, he qualified for Special Forces and was deployed to Vietnam in 1964. It was in July of that year that he displayed exceptional courage and tenacity in defending an American training camp, earning him the prestigious Medal of Honor.

Donlon passed away on January 25, 2024, just five days shy of his 90th birthday.

In the early hours of July 6, 1964, Captain Roger Donlon found himself facing a daunting challenge. As the commander of the detachment at Nam Dong training camp in Vietnam, he was thrust into a near-fatal defence when the camp came under attack. The North Vietnamese Army, in collaboration with Viet Cong guerrillas, sought to overrun the American Special Forces training centre. This marked the first instance of such cooperation between the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong in the south.

Amid the intense firefight that ensued, Donlon, leading Vietnamese trainees along with Australian and Special Forces advisers, displayed remarkable resilience. The camp, housing 360 CIDG trainees, 12 Green Berets, and one Australian adviser, was under siege by 800 North Vietnamese troops. Donlon, on guard duty, immediately took charge, orchestrating the movement of ammunition from burning buildings and establishing defensive lines.

Despite sustaining injuries during the chaos, including a severe stomach wound, Donlon continued to lead. He thwarted a Viet Cong attack on the main gate, eliminated sappers, and provided crucial cover for the withdrawal of wounded comrades. Throughout the battle, he endured multiple wounds, including a mortar blast to his left shoulder and shrapnel in his leg.

Undeterred, Donlon crawled through enemy fire, directed mortar fire, and tirelessly moved between positions, ensuring the defence held. When helicopters finally arrived to evacuate the wounded, the toll on the enemy was significant, with about 60 troops dead, along with 57 South Vietnamese, two Americans, and their Australian adviser.

President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Donlon the Medal of Honor on December 5, 1964, making him the first of 268 recipients during the Vietnam War. Donlon continued his military career, retiring as a colonel in 1988. Reflecting on the honour bestowed upon him, he acknowledged wearing the award on behalf of those who didn’t return, emphasizing the shared sacrifices of his fellow soldiers.

Top of Form

Battle of Nam Dong – July 1964: WO2 Kevin Conway – the first Australian to die of enemy action in the Vietnam War.

A nine-page account by US Captain Roger Donlon of the Nam Dong Battle can be found at https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/images.php?img=/images/213/2130413003.pdf. He records that an Australian AATTV member was killed in the battle., noting: “Besides the 12 of us in Team A-726, there were only two other westerners in the camp: Kevin Conway, an Australian warrant officer who represented his country the way we did the United States, and Gerald C. Hickey, an American anthropologist expert on the Vietnamese mountain tribes.”

The Australian War Memorial Records notes:

13097 Temporary Warrant Officer Class 2

Kevin George. Conway, Age 35.

Australian Army Training Team Vietnam

Attached to US Special Forces. He was killed in action at Nam Dong, Thua Thien Province on 6th 6 6 July 1964. He was the first combat casualty. He held the Medal of Knight, National Order of Vietnam , Cross of Gallantry with Palm. He was also awarded a Campaign Service Medal with clasp South Vietnam (this is a very rare award only 68 issued, all to the AATTV). He also was awarded the US Silver Star and the Vietnamese Armed Forces Honour Medal, Kevin Conway was recommended for the Victoria Cross, but this was denied at that time, because Australia was not at war. The Australian Government saw fit not to award Conway with anything, but the South Vietnamese awarded him their highest award being the National Order of Vietnam.

Warrant Officer Class 2, Kevin Conway becomes the first Australian to die as a result of enemy action in South Vietnam.

Hi Ernie,

I didn’t see your comment. I’ve just sent the following:

“Hi, The article about America’s first MoH recipient in the Vietnam War … fails to mention that in the same battle, Australia’s first KIA was lost [WO2 Kevin Conway]. Suggest this warrants it’s own story as a matter of national significance and pride.”

Cheers, Bruce

Hi Bruce, Regarding WO2 Ken Conway – the first Australian soldier to be killed-in-action in Vietnam, you might be interested in the following comments a few years ago by Andrew Laming – MP, on his website ( ie: Federation Chamber – 25 October 2018) regarding WO2 Ken Conway:

“Lastly and very importantly, by moving the year when the Vietnam War began, we are now just starting to recognise the breadth and dimension of service in that war. It’s now officially 1962. It wasn’t always 1962, because we were not officially at war. But I want to say today that Australians were serving then and Australians were dying. The first casualty in the Vietnam War was a gentlemen by the name of Kevin Conway from Wellington Point in my electorate. At the moment, we are reapplying for his bravery to be recognised. I would like to read into the Hansard the importance of his gentleman’s service. Sergeant and Temporary Warrant Officer Class 2 Kevin Conway was killed in action in 1964 in the Battle of Nam Dong. As a member of the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam, he was placed on his own to work with American consultants ((sic)) in building the capacity of the South Vietnamese to defend themselves. He was the first Australian, as I’ve said, to die in that war.

He left school at 15 years of age and attempted to enlist for the Second World War in 1943, but was too young. So he joined what was called the post-war army. It is unclear whether he was able to serve in Korea, but he did serve in Malaysia and was awarded the appropriate clasp. He was an efficient and conscientious soldier. He had a practical, common-sense approach to problems. He was the kind of Aussie you would want to send to the front line. He was the kind of Australian who could work shoulder to shoulder with the Americans and do our nation proud, which is precisely what he did in an incredibly remote part of Vietnam, close to the Laotian border. What we didn’t realise at the time was that up to a quarter of the South Vietnamese that he was helping to train were actually Vietcong. The very men who the Australians and Americans were trying to assist to build their nation, and to get their nation on its feet and able to defend from what they saw as a northern threat, had already technically deserted but remained to ambush these serving personnel when the time was right. When a bullet was heard and shot in anger, these South Vietnamese were instructed to pull their shirt off, identify as Vietcong and slit the throat or shoot at point-blank the Australian or the American they were standing next to. Imagine serving in that context!

Conway was recommended for the Victoria Cross by the AATTV and by Colonel Ted Serong, in particular, for not only running towards a mortar trench but urging others around him to organise themselves and defend. The US officer next to Conway, Captain Donlon, became the first recipient of the Medal of Honour in the Vietnam War for his actions alongside him. Several other Americans also received an award. While Conway received the highest bravery award that Vietnam can offer, he received nothing from Australia.

When Colonel Serong visited the scene of the battle, he said Conway and a US Master Sergeant fought their way through the Vietcong just to get to a mortar pit where they began their assignment of firing illumination flares so they could see the enemy. When another Vietcong assault brought the attackers to within grenade-throwing distance of the trench, Conway had two choices: pull out his firearm and defend himself, or continue operating the mortar. He chose the latter. We have been through the archives in the last month looking for a previous recommendation for a Victoria Cross for this gentleman. Archives have confirmed that they cannot find it. On those grounds, we are now applying directly to the Department of Defence to ensure that the valour of Kevin Conway is recognised.”