The General Atomics Mojave drone will change everything. With the ability to reach out and touch the enemy from half a world away, the Mojave is the perfect weapon for conducting recon missions or armed assassinations. This video will analyze the drone’s capabilities and limitations, along with some advantages it has over the Reaper drone and how it works in the field. It will also discuss the recent upgrade that allows the drone to carry two Mini-gun pods under each wing using two of its seven hard points.

In December 1941, a daring recon mission skimmed the French coast. A Spitfire, its camera locked on target, captured the image of a mysterious device that would send shivers down the spines of Allied commanders. This single photograph ignited a sequence of events leading to one of the most audacious raids of World War II: Operation Biting, also known as the Bruneval Raid.

Australia has endorsed a historic treaty requiring patent applicants to disclose the origins of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge in their applications.

The recently signed Treaty on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources, and Associated Traditional Knowledge, supported by members of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), aims to benefit Australian First Nations peoples by mandating the disclosure of traditional knowledge sources in patent applications.

Signed in Geneva, Switzerland, this treaty represents a significant step towards legally recognizing Indigenous traditional knowledge within the international intellectual property framework.

“First Nations Australians have been innovating for thousands of years. This landmark treaty will, for the first time, acknowledge Indigenous contributions within the international intellectual property system,” stated Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong.

“This historic agreement is a vital component of the government’s commitment to a First Nations approach to foreign policy,” she added.

Alongside Foreign Affairs Minister Wong, Trade Minister Don Farrell and Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney emphasized that the treaty would enhance the unique and diverse export offerings of First Nations peoples and further protect the traditional knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia.

“Safeguarding First Nations intellectual property is a practical measure that will help Indigenous people, businesses, and exporters share in the benefits of trade,” said Mr. Farrell.

Ms. Burney reaffirmed the government’s commitment to recognizing Indigenous intellectual property rights and supporting related initiatives.

According to WIPO, genetic resources include medicinal plants, agricultural crops, and animal breeds, which are intrinsically linked to traditional knowledge through their use and conservation by Indigenous peoples and local communities over generations.

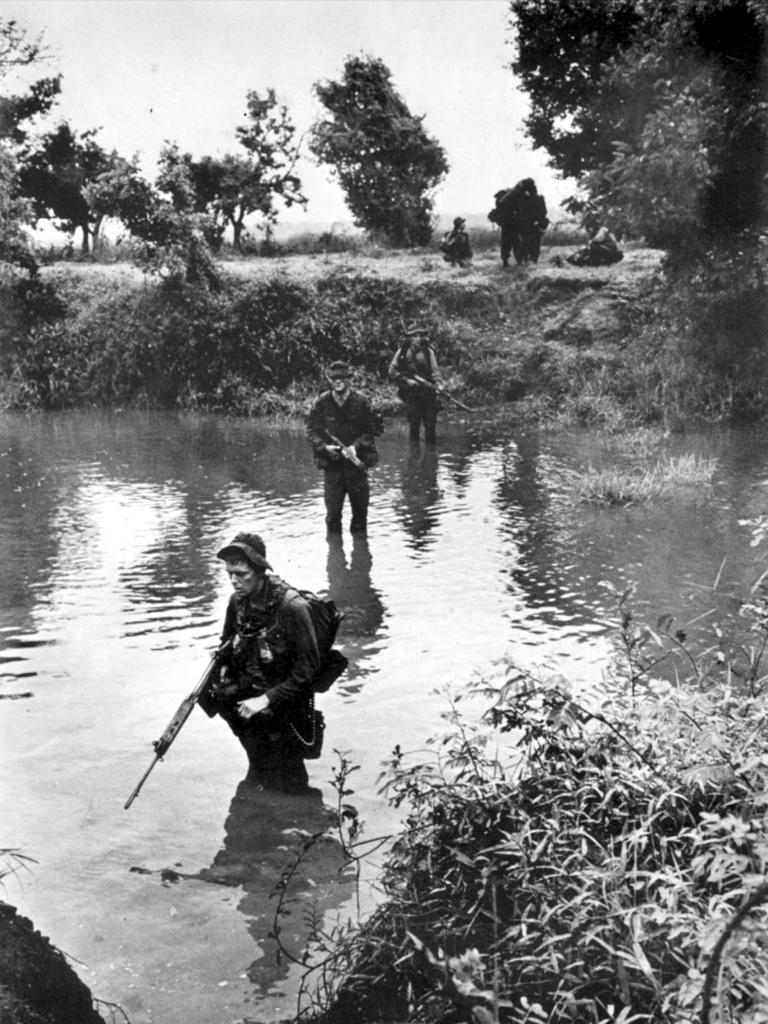

In April this year, after 15 years of search efforts, and almost on the 56th anniversary of the Battle of Balmoral, a team including an Australian veteran and the son of another have helped Vietnamese authorities to identify the resting place of a large number of fallen Vietnamese soldiers in Bình Dương province.

The story begins in May 1968 when a series of battles was fought between the 1st Australian Task Force and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and Viet Cong (VC) forces.

Members of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR) had established a defensive fire support base named Balmoral and fought against (principally) the PAVN 7th Division. Engagements occurred on 26 and 28 May.

Following the second assault on 28 May, 3RAR counted 42 PAVN dead on the battlefield, mostly in front of Delta Company. After the engagement ended, members of 3RAR buried 20 deceased PAVN members in a single bomb crater that was covered over during the subsequent occupation of the base – its location eventually lost.

Since then, over many years 3RAR veterans have sought to properly recognise the service of those fallen Vietnamese soldiers and to recover the bodies for their families.

Beginning in 2009, 3RAR veteran Brian Cleaver along with others provided information to local authorities who undertook numerous searches with limited success until 2019.

In 2020 a team that included 3RAR veteran John Bryant, Luke Johnston (son of 3RAR veteran David Johnston) and Glenn Hines, with support from Ms Trần Thị Phương Như, identified the correct burial location.

Information used to determine the location included battlefield photographs and accurate recollections of John Bryant, a detailed on-ground survey by Luke Johnston and desktop research assistance by Glenn Hines.

The Defence Section of the Australian Embassy in Hanoi facilitated contact between this team, the Steering Committee 515 and the Vietnamese Ministry of National Defence advocating for a new search effort.

Authorities from Bình Dương province began the new search on 13 March this year, and on 1 April they recovered the first remains of one of the fallen. Since then, some 20 sets of human remains have been found and the search is ongoing.

The Embassy’s Facebook page stated that the long-term effort by the 3RAR veterans and their families is testament to the respect they held for the fallen Vietnamese soldiers and that their determination to find the remains brings great credit to the team.

‘The search itself has been conducted in extremely difficult conditions, and the on-ground search team provided by the Vietnam People’s Army have been thoroughly professional in their duties, undertaking the task with diligence and respect,’ the Facebook read.

In his father’s footsteps

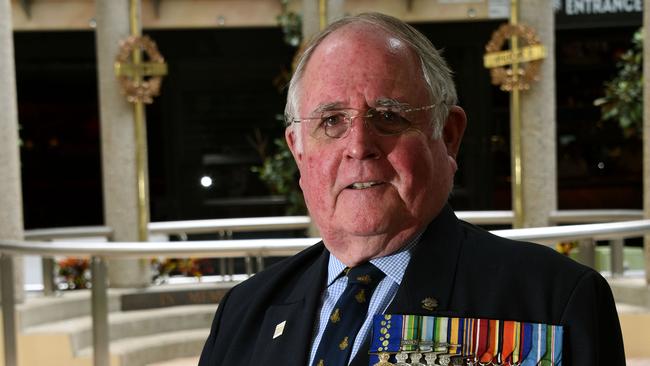

As a boy growing up, Luke Johnson was puzzled by the impact the war had on his dad, but as he got older, he learned that it was related to his father’s service in Vietnam.

In his 20s, to understand his father’s experience, he began a quest to retrace his dad’s time in Vietnam, using service and battle records, and his dad’s personal descriptions. Until his father David passed away in 2016, he would recount in detail his Vietnam journeys and impressions, which did a lot to help his father come to terms with and resolve his posttraumatic stress syndrome.

‘He lived vicariously through my travels,’ said Luke. ‘I would contact him daily when I was here [in Vietnam] and would come back with photos and all the places he’d lived, patrolled and fought, and he could see it, see the change in the landscape and see the warmth of the people I was meeting with. It meant a great deal to him.

‘While Dad never got to see the results of this recovery effort, I can tell you, based on his reaction to my previous efforts and time out here, he would have been emotional, he would have been happy, overjoyed, and sad, and that’s the response that I had as well.

‘It’s been an incredibly well-received result for incredibly grateful Vietnamese people.’

Logic leaves ‘The Science’ of climate in the dust.

It is the gag order of the pseudo eco-scholar: “The Science is settled.” This is not science as we once understood it. In that discipline something could be proved false through observation and experiment. No, this is “The Science”: science as deity.

In the 20th century Karl Popper transformed the philosophy of science around the idea of falsifiability, saying: “It must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience.”

The first rule in Popper’s The Logic of Scientific Discovery is: “The game of science is, in principle, without end. He who decides one day that scientific statements do not call for any further test, and that they can be regarded as finally verified, retires from the game.”

So, you can spend a lifetime counting white swans, but find one black one and the thesis that all swans are white is destroyed. The black swan event happened when Europeans first encountered the impossible animal in Australia.

Prove one assumption wrong and a whole set of conclusions collapses. The Science is not real science. It is a set of beliefs, a faith. Those who demand we agree it’s settled are no different from a Catholic bishop declaring: “Roma locuta est; causa finita est” – Rome has spoken; the cause is finished.

The zealots who invoke The Science as a gag order have never read the research or wilfully ignore its infuriating uncertainty. This uncountably large group includes battalions of politicians, academics, activists, journalists and a few dozen billionaire energy-hobbyist carpetbaggers.

Take the deeply entrenched belief that global warming is causing more extreme weather. This is so ubiquitous as to be unquestioned. It is an article of faith and there is almost no weather event nowadays that does not come with a blizzard of declarations it is proof of climate change.

Among myriad examples, let’s pick Tropical Cyclone Jasper, which hit far north Queensland in December. It dumped a massive amount of rain and none of what follows denies the fact it caused great damage and suffering. In its wake the Red Cross released an Instagram video declaring “Disasters like Ex-Tropical Cyclone Jasper in Far North Queensland are happening more often due to climate change”. Greenpeace called it a “frightening portent of what’s to come under climate change”. The Climate Council warned “climate change is making (tropical cyclones) more destructive”.

None of this is true.

No one denies Ex-Tropical Cyclone Jasper caused great damage, but the science doesn’t back up claims it could be attributed to climate change.

If The Science of global warming has a bible then surely it must be the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. It is the latest accumulation of all the best research and it runs to a mind-numbing 2391 pages.

On page 1586 it says: “(Tropical cyclone) landfall frequency over Australia shows a decreasing trend in Eastern Australia since the 1800s, as well as in other parts of Australia since 1982. A paleoclimate proxy reconstruction shows that recent levels of (tropical cyclone) interactions along parts of the Australian coastline are the lowest in the past 550-1500 years.”

Pause on that. Not only does observation show there are fewer cyclones since the industrial revolution began belching extra carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, there is evidence to suggest cyclone activity in Australia is at its lowest ebb since the days of the Tang dynasty and the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

The CSIRO echoes that finding in its State of the Climate Report 2022 and adds: “The trend in cyclone intensity in the Australian region is harder to quantify than cyclone frequency, due to uncertainties in estimating the intensity of individual cyclones and the relatively small number of intense cyclones.”

What of droughts? The IPCC finds southwestern Australia has been drying out since the 1950s and there is evidence that the length of droughts in southeastern Australia has “increased significantly”. But it says “the Millennium drought in eastern Australia was not unusual in the context of natural variability reconstructed over the past millennium” and concludes “there is currently low confidence that recent droughts in eastern Australia can be clearly attributed to human influence” (p1089).

In summary, on page 1663, it says there is low confidence in observed trends, or projected changes, to droughts in central and eastern Australia as the climate warms. In northern Australia there is medium confidence of a “decrease in the frequency and intensity of meteorological droughts”. So, more rain for the Top End then.

The report notes the major drivers of drought in Australia as well-known natural climate events: “During the last millennium, the combined effect of a positive (Indian Ocean Dipole) and El Nino conditions have caused severe droughts over Australia” (p1104).

What of bushfires? “Extreme conditions, like the 2019 Australian bushfires and African flooding, have been associated with strong positive (Indian Ocean Dipole) conditions” (p1104).

And, in case you were wondering, “There is no evidence of a trend in the Indian Ocean Dipole mode and associated anthropogenic forcing” and “The amplitude of the El Nino–Southern Oscillation variability has increased since 1950 but there is no clear evidence of human influence” (p1104).

Let’s be clear. There is plenty of evidence in the IPCC report demonstrating the climate is changing, that the world and Australia are getting warmer, and that industrial activity has played a part in forcing some of it. We should take that seriously. In response Australia should do its proportionate share in cutting greenhouse gas emissions without destroying our local ecology or impoverishing the nation.

But here is the good news: we are not facing a climate Armageddon. Again, this is not just my view but one shared by British professor Jim Skea, who was appointed chairman of the IPCC last year.

“The world won’t end if it warms by more than 1.5 degrees,” Skea told German weekly magazine Der Spiegel last year. “It will however be a more dangerous world. Countries will struggle with many problems, there will be social tensions.

“And yet this is not an existential threat to humanity. Even with 1.5 degrees of warming, we will not die out.”

Skea worries the zealots are doing their cause a grave disservice. “If you constantly communicate the message that we are all doomed to extinction, then that paralyses people and prevents them from taking the necessary steps to get a grip on climate change,” he said.

What it is also designed to do is scare people out of questioning absurd statements and bad policies.

Here there is another assault on reason by ideologues. In this game of witch burning, questioning a policy response to global warming is evidence of the crime of climate change denial. Their argument can be expressed as a syllogism.

Premise 1: Climate change is real.

Premise 2: Renewable energy combats climate change.

Conclusion: Therefore, to question renewable energy is to deny climate change.

This is the logical fallacy of a false dichotomy; it ignores the possibility of neutrality or nuance. But logic, like science, has long since departed in this debate. This is all about faith.

Several NATO member states supply weapons to Ukraine without conditions on their use, while others stipulate, they can only be used against Russian targets within Ukraine’s borders. Recently, there has been a growing demand for Ukraine to have the freedom to use these weapons as it sees fit for self-defence.

On Thursday, Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavsky stated that Prague had “no problem with Ukraine defending itself against an aggressor” and supported Kyiv’s use of munitions supplied by his country to attack targets in Russia.

Earlier in the week, French President Emmanuel Macron advocated for allowing Ukraine to strike Russian positions inside Russia using Western weapons. During his state visit to Germany, Macron argued that Ukraine should be able to “neutralize military sites where missiles are fired,” speaking alongside German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Berlin.

Scholz, while more cautious, said he had no legal objection to Macron’s stance and affirmed that Ukraine was “allowed to defend itself.” The UK also supports Ukraine’s right to determine how to use British weapons, including striking targets inside Russia.

On Wednesday, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken mentioned that the policy on Ukraine’s use of American weapons is continually evolving, hinting that Washington might consider allowing Ukraine to use US weapons in attacks on Russian territory.

However, not all are in favour of this idea. Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto labelled it a “crazy idea for the Ukrainians to fire Western weapons into Russia’s interior.”

Russia has issued stern warnings to Ukraine’s allies against permitting Kyiv to conduct strikes on Russian soil using Western weapons. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov cautioned that such actions would “ultimately be very damaging to the interests of those countries that have chosen the path of escalating tensions.”

ED: From a mate in California who told me that a whip around at his local VFW raised $3225 donation for Trump Campaign

By Greg Allison – Tahoe Mail

In a historic and unprecedented event, former US President Donald Trump has been found guilty on all counts in a landmark criminal trial. This marks the first time in history that a former or sitting president has been convicted of a crime, sending shockwaves through the nation. While reactions varied significantly across the political spectrum, conservatives have been particularly vocal in expressing their outrage and solidarity with Trump.

Trump faced 34 counts of falsifying business records, a charge that the prosecution claimed was part of an illegal conspiracy to undermine the 2016 presidential election. This included allegations of concealing a hush money payment to adult film star Stormy Daniels. However, the defence was hindered by a lack of a robust counter-narrative.

The conviction, a significant and unprecedented development, saw each juror confirm their decision to convict Trump. In a dramatic moment, Trump turned to face each juror as they delivered their verdict.

Trump has accused Judge Juan Merchan of “not requiring a unanimous decision” on the charges, a claim that has resonated with many of his supporters. While this accusation is somewhat misleading—since the jury must unanimously agree that certain “unlawful means” were used—it has fuelled the belief among many conservatives that the trial was unfair.

The timing of the July 11th sentencing, just days before the Republican National Convention on July 15th, has raised suspicions of political motivation. Many argue that this timing is strategically aimed at damaging Trump’s reputation and hindering his potential 2024 presidential run.

Supporters of Trump also point out that while individuals like Hunter Biden and those involved in the Jeffrey Epstein case remain unscathed, Trump is being targeted for actions they see as comparatively minor. This perceived double standard has only strengthened their resolve.

Despite the celebratory reactions from left-leaning commentators and some segments of the public, Trump’s support base has shown a remarkable surge in solidarity. The Trump campaign’s donation site crashed shortly after the verdict, indicating a groundswell of financial and moral support. Contrary to claims by commentators like Rachel Maddow that the verdict would dissuade undecided voters and benefit President Biden, many believe this event will galvanize Trump’s base and increase his chances in the next election.

While Trump’s conviction has indeed shaken the nation, it has also ignited a fervent response from his supporters. They view this as a politically motivated attack and are more determined than ever to support him. The coming months will undoubtedly see this issue play a significant role in the political landscape as the nation heads towards the next election cycle.

THERE are few people so annoying as those aficionados of the ancient martial art, ‘Aorta’

THERE are few people so annoying as those aficionados of the ancient martial art, ‘Aorta’

For anyone who believes they have never heard of ‘Aorta’, its practitioners are all around us, just like carbon dioxide, but less useful.

Identifying them is relatively simple if you know the clues, such as where to look and identifying sounds.

Start in pubs, bars, even ADF messes of all kind, officers’ messes included.

You’ve all heard them but possibly never understood their message.

And the worst are the wannabes who copy the brain flatulence of others.

CLICK LINK to continue reading

Australian Defence History, Policy and Veterans Issues (targetsdown.blogspot.com)